A struggle for books

December 7, 2020

by James Tobin, writer and historian

Photos from the Bentley Historical Library

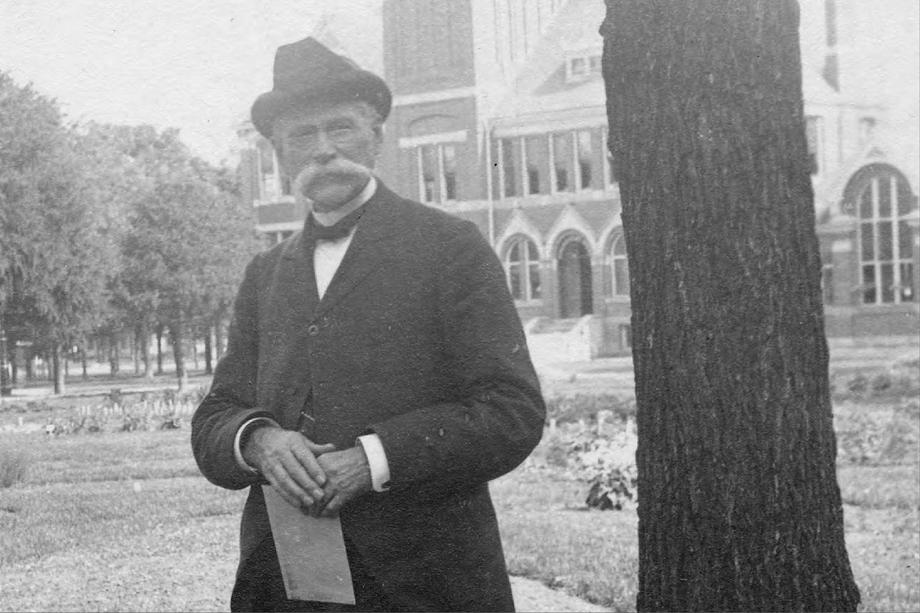

In the fall of 1905, at the age of 69, the energetic Raymond Cazallis Davis was finally slowing down. For nearly 40 years he had served as assistant librarian, then chief librarian, of the University of Michigan. With retirement approaching, he bent his 6-foot-two-inch frame into his chair in the General Library — a landmark he had helped to create — and began to draft his final report to the faculty.

Davis was one of the most distinguished academic librarians of his day, but he wore his prestige lightly. He had "bright eyes with a friendly twinkle in them," a colleague remarked. He was known as a kind boss, "modest, friendly, agreeable." He liked the students and they liked him.

Still, he was ready to be done with his job. During summer vacations he and his wife had always fled to his native New England for brief escapes from "the almost feverish rush of university life at Ann Arbor." Now the time for a real rest had come. But first he wanted to sum up his labors of all those years.

He wrote: "If I were to characterize in a few words my work as librarian my answer would be: A struggle for books. If my existence should be so prolonged that impressions made upon me grow faint and disappear, I am sure that the memories of that struggle will remain."

"A struggle for books" — to acquire them, protect them, catalog them, send them out and bring them home, and most of all to make sure there was room for them all: those four words tell the story of the University Library in every era, whether the stacks held 3,400 books — the size of the original collection — or 14 million, as they do today.

The paradox is that there have never been enough books for the faculty and students — or serials, microfilms, photographs, documents, maps, films, floppy disks, recordings, prints, papyri, ebooks — and there has never been enough room for all of them.

Books, but no building

Michigan's first president, Henry Philip Tappan, declared that "a library supplies the daily food of the mind." But for years and years, the university's books were misfits in search of a home.

First they were stowed in spare rooms in professors' houses, then in old North Hall, a classroom building that stood roughly on the site of the north wing of Angell Hall. During the Civil War, when the Law Building was erected at the corner of State and North University, the books took up residence there, much to the rising irritation of law professors and students.

By 1875 the crowding of books and readers was intolerable. The collection had doubled in just the last five years, from 43,450 to 89,400. New volumes were crammed on every available surface. Yet students complained that their professors were requiring them to read books the library didn't have, and professors needed more books for their own studies. Every member of the faculty was given fifty dollars annually to buy books in his specialty, but that, one observer said, was "ludicrously inadequate...to keep...in sight of the boundaries of advanced thought, which are fast receding..."

To safeguard the books, it was forbidden to remove them from the building unless you were a professor or one of a few favored students. So most students did their reading in the Law Building's reading room, a space so badly ventilated that "the overcrowding witnessed there nearly every day renders the foulness of the atmosphere a constant subject of remark," wrote an editorialist in the Chronicle, U-M's student newspaper in that era. "One who is at all sensitive to impure air cannot stay longer than an hour or two without getting so sick or drowsy that to remain longer is so much waste time."

Worst of all, the same student writer reported, "is the everlasting rustling of newspapers. It is as if a hurricane had burst into a paper mill... And just as you have got fairly absorbed in your historical study, some obstreperous 'law' or 'medic' plants a newspaper or two directly on the book before you."

Students were hearing rumors that a stand-alone library would soon be built. That would be good, the same writer said, but the purchase of many more books would be better. "We congratulate future classes on their good fortune, and hope they will not have the mortification to see all the surplus wealth of Michigan squandered on a fine building, to the impoverishing of the contents."

The collection united

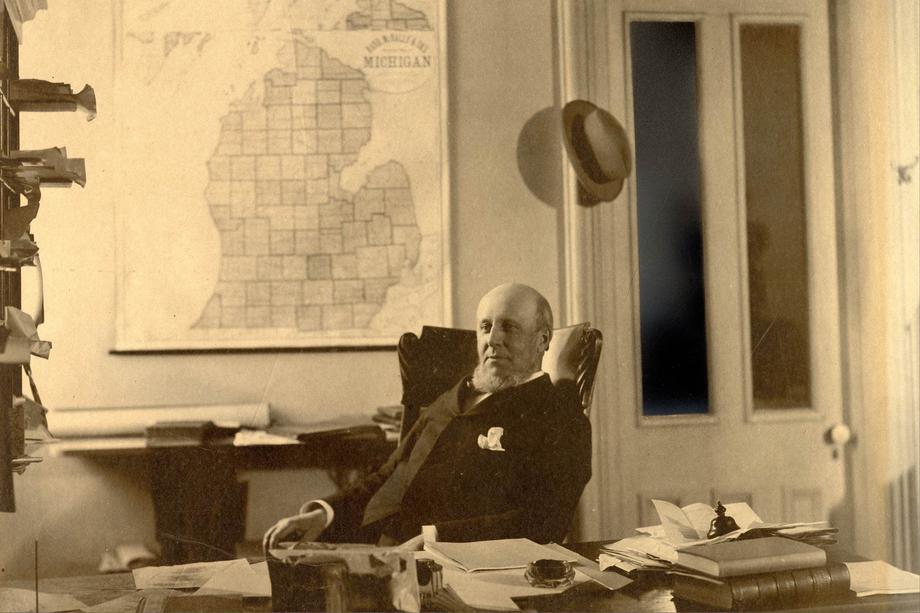

The rumors were true, but only insofar as President James Burrill Angell was determined to build a free-standing library. He had yet to find the necessary funds. "The library must be the center of the intellectual life of the university," he insisted to all who would listen. "It should therefore be cared for with the most scrupulous pains and be nourished with the largest generosity."

But five more years would pass — and the books would escape two near-disasters by fire — before Angell's pleas for funding finally were answered.

Finally, when Angell was serving as U.S. minister to China in 1880-81, the Michigan legislature allotted $100,000 for construction of a fine, fireproof building plus $5,000 for new books. Regent George Duffield, Jr., was so delighted he took a quill pen made from the feather of a Lake Superior eagle up to Lansing for Governor David Jerome to use when he signed the appropriation.

The design contract went to William Robert Ware and Henry Van Brunt, of Boston. Their work to date included Harvard's Memorial Hall, an impressive example of the style called High Victorian Gothic. It was a look much prized for college campuses, and it certainly influenced Ware and Van Brunt as they sketched their plans for the General Library.

Under the direction of James Appleyard, a Lansing contractor who had supervised construction of the Michigan Capitol, the building rose brick by brick through two years of construction that was often delayed by unusually heavy rains. (Appleyard won the contract with a bid of $85,375.50.)

Gradually, passing students and faculty saw a distinctive shape emerging. It looked a bit like a red-brick battleship plowing northward through the center of the Diag. Stocky twin towers jutted up from the half-oval of a great reading room. Above the curving northern face, two tiers of windows surveyed the scene. In its bulky way it was lovely, an instant landmark.

Inside, the core was built strong enough to bear a giant burden of books. Three fireproof tiers made of stone and hammered glass, 27 feet high, held nine ranges of iron stacks three feet apart — enough space for about 80,000 books. (There's no need to imagine what those stacks were like. They were so durable that they're still holding books in the north wing of today's Hatcher Graduate Library.)

No money was spent on artistic flourishes. The building's austere beauty, it was observed, depended on "the symmetrical disposition of masses, according to the manner of the Romans in the construction of their public bathes...with a view to the creation of a building which should be strong and honest and at the same time a work of art."

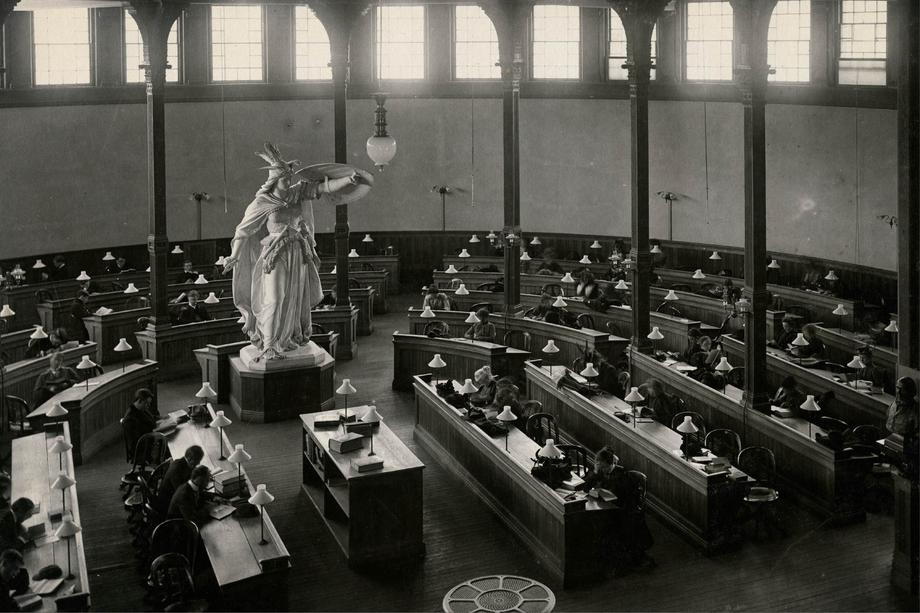

A book lift in a brick shaft carried books from the upper stacks to the delivery desk. There was an art gallery; two rooms for seminars; and offices for the librarians. The jewel of the building was the great semi-circular reading room, eighty feet in diameter and 24 feet from floor to ceiling. The overhead windows admitted natural light for up to 210 readers seated at six semi-circular rows of reading desks. (That was only twice the number of readers who could fit in the old reading room of the Law Building, but the newspaper readers had been given their own new space in University Hall, so there would be little griping.) Gas lighting was installed for evenings and late afternoons in winter. (Inadequate from the start, these fixtures would be replaced by electric lights in 1897.)

Above the reading room there was a curving gallery that would house the university's art collection, an assemblage of originals and copies of European masters, most of them given by private donors. The delightful acoustics in this space would soon inspire its name — the "Whispering Gallery."

By October 1883, a year late, the new building was ready to receive books. In the Law Building, the staff had been reclassifying the collection, then dusting and marking each book for proper placement in its new home. Now stacks of bushel baskets were lined with heavy paper, then filled with books. The baskets were loaded on horse-drawn drays; then teamsters hauled their literary freight a couple hundred yards to the southeast. There, Elizabeth Farrand, an assistant librarian, took charge of them, seeing that helpers got each to its proper shelf. (Farrand would graduate from U-M's Medical Department and write a definitive history of the university.)

One young helper was so gung-ho about the transfer, Davis remarked, that "his enthusiasm communicated itself to all the other employees, and especially to the teamsters, who galloped their horses going and coming." So the whole operation took only five days, half the time Davis had predicted, and library service was virtually uninterrupted.

Watching all this from afar was the historian Andrew Dickson White, who had left the Michigan faculty during the Civil War. He was now president of Cornell University, but he was still deeply fond of U-M, and he wanted to do something for the new library in Ann Arbor. So, with a couple of friends, he collected enough money to donate a peal of five bells that ranged from 210 to 3,071 pounds for the library’s west tower. Inscribed on the largest bell were these words in Latin: “Call together those who are studious of all good things both human and divine.” They would toll the “Westminster Quarters”— four permutations of four pitches in E-major — at every quarter-hour for nearly 40 years.

The new building and bells were dedicated on December 12, 1883. In his remarks, President Angell no sooner had celebrated the library's completion than he declared the work of expansion only begun.

"Our library has more than doubled in size during the last ten years," he said, "but to meet the varied wants of a university like this it needs still to be much larger."

More money, more books, more space

With a grand new library just completed, why the need for more space already?

The reasons had to do with Angell's own leadership. He was making good on the vision of his predecessor, Henry Philip Tappan, who had imagined Michigan as a publicly-funded rival to the great private centers of learning in the U.S. and Europe. Under his guidance, new departments were springing up. Faculty members were doing more research. Elective courses were multiplying. Women were enrolling in growing numbers. High school graduates could now gain admission to U-M without taking entrance exams. The number of students was surging.

So Angell and Davis kept pounding the drum for more money, more books, more space.

Angell to the regents, 1891: "No library in the country is so much used. It is my duty to notify you that at an early day it will be necessary to make an addition to the library building."

Angell to the regents, 1895: "The embarrassment, to which I have called attention in previous reports, arising from the crowded condition of the library, of course grows more serious every year."

Angell to the regents, 1896: "We have to remember that the library is the great central power in the instruction given in the university..."

Davis to Angell, 1897: "The shelving capacity...has been exhausted. If more temporary shelving can be provided, we can better our present condition, but the congested state will still remain, and the conditions for administering the library, which are now hard, will be very hard."

Angell to the regents, explaining how the "seminary" (seminar) method of teaching exacerbated the demand for more library space, 1901: "Few innovations in the method of university instruction have been more fruitful of good results... We should not fall behind other institutions in reaping the largest results from it."

So it went, year after year, with piecemeal additions never quite meeting the need for more of everything.

In 1909 Angell finally turned over the presidency to Harry Burns Hutchins, former dean of the Law School. Now Hutchins had to contend with this grim fact: The once-new library, much of it built of wood, was entering its maturity as the campus's largest firetrap. Cramped spaces were one thing, but the risk of a catastrophic fire was another. This simply would no longer do.

So in 1915, the regents inveigled the state legislature to fork over $350,000 to replace the library, beloved chimes and all.

Shortly thereafter, William Warner Bishop, a preeminent figure in the field, was appointed University Librarian and told to make it happen.

A fulcrum figure

Born in his father's (and Mark Twain's) home town of Hannibal, Missouri, but raised mostly in his mother's home town of Detroit, Bishop earned two degrees from Michigan (B.A., 1892, M.A., 1893). As a student he was so well thought of that Raymond C. Davis let him roam the stacks at will — a rare privilege for an undergraduate.

With a master's in classics, he began his career as a professor of New Testament Greek at little Missouri Wesleyan, where he supplemented his pay as acting vice-president and part-time librarian. Then a research sojourn at the Vatican Library nurtured his love of libraries. (Once, upon asking for a particular manuscript, he was tickled to get his slip back with a note in blue pencil: "Missing since 1682.") So when illness prevented him from completing a doctorate, he shifted to librarianship.

It was the right move. Before long, he was chief cataloger of the Princeton University Library, then Princeton's head of reference, then superintendent of the reading room of the Library of Congress. (He lent books to Presidents Theodore Roosevelt, who asked for books by his White House guests so he could read them in advance; William Howard Taft; and Woodrow Wilson, who wanted mysteries. Bishop picked them out himself.) Married in 1905, he was soon the father of a son, William Warner Bishop, Jr., who would grow up to be a distinguished professor at the Law School. He published regularly in his field, including a standard reference work, Practical Handbook of Library Cataloging.

Important as Raymond Davis had been, Bishop became arguably the fulcrum figure in the library's long history. It was he who not only brought the university's central library of the 20th century into being, but laid the foundation of a library system suited to an era of exploding information ��— including a Department of Library Science that would evolve into today's School of Information.

Space for a million books (and a familiar theme)

Bishop's predecessors had left him something of a mess. The collection, now up to 350,000 volumes, was strong in some areas but decidedly weak in others. A gloomy backlog of 30,000 books sat waiting to be cataloged. The others bore the markings of the Dewey Decimal System — no good in the eyes of Bishop, a devotee of the Library of Congress system. He had a small, underpaid staff that included only five professionally trained librarians.

And he had to replace that cramped old building, beloved but beyond inadequate.

The regents had already awarded the design contract to the firm of Albert Kahn, the great Detroit architect best known for industrial facilities like Ford Motor Company's River Rouge plant. At U-M he had designed Hill Auditorium, the Natural Science Building and West Engineering, among others. (More Kahn designs, including the Clements Library, Angell Hall, University Hospital and Burton Memorial Tower, would follow.)

For three months, two or three times a week, Bishop and Kahn put their heads together over plans. Bishop traveled north, east and west to study library systems at Harvard, Wisconsin, Illinois, Montreal, and others.

They saved an estimated $150,000 by keeping the massive, fireproof stacks at the old library's core. To these they added two new sets of stacks on either side of the old. Fire prevention guided important choices — reinforced concrete for the main structure; steel-and-glass enclosures for the stairwells. Large windows would let in a great deal of light, especially in the seminar rooms in the upper stories.

Much of the old building was demolished in clouds of dust. Then came the first phase of construction — the new stacks on the west side. U.S. entry into World War I slowed everything, but the work ground on.

By now, U-M had persuaded the state to give $200,000 on top of the original appropriation. The regents tossed in $65,000 more to meet the total cost of $615,000.

-01.jpg)

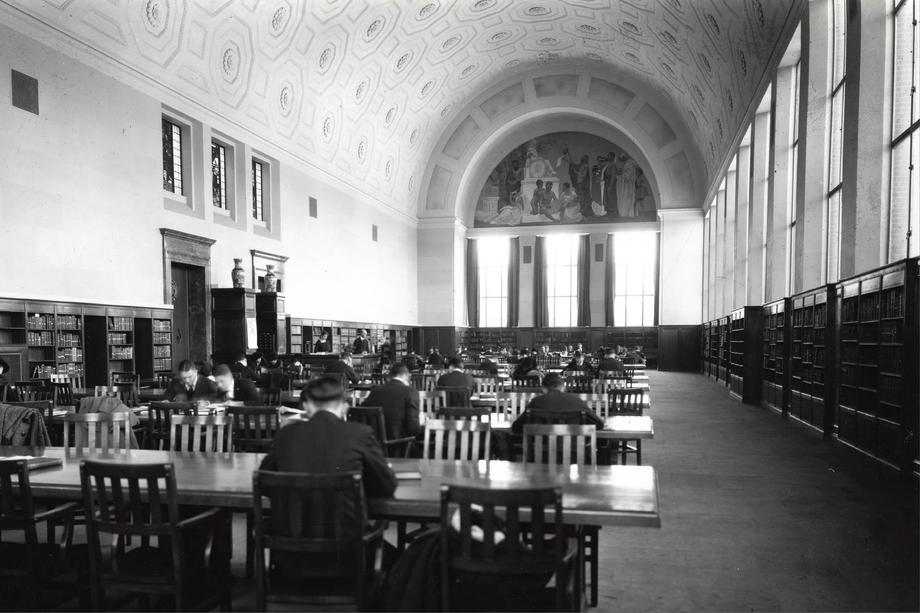

The exterior was in the Kahn style — not ornate but handsome, hulking, practical. The interior design suggested a museum of fine art. No doubt some called it dignified; others might have called it cold. Builders lined the lobby with marble quarried in Tennessee and decorated in a Pompeiian motif that would perplex later generations of students. Two murals commissioned for the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 — "The Arts of Peace" and the "The Arts of War" — were lugged over from University Hall, where they'd been for years, and installed just under the barrel-vaulted ceiling of a cavernous reading room where 300 could sit at a time.

On Friday, January 7, 1920, President Hutchins cancelled afternoon classes so students could attend the ceremonies in Hill Auditorium at 3 p.m. Speakers said the new building had room for a million books, an extraordinary number.

But here again was the old theme: "In building the library," the Michigan Daily reported, "provision was made for future enlargement...so that it will hold twice this number of books."

Technology and change

Inside the library, a new era dawned. While construction was still underway, Bishop pointed out that “few people in library work realize the part which the electric light, structural and sheet steel, electric elevators, heavy plate glass, and the like have played in revolutionizing library methods. Much of our modern theory and practice is due to the engineer and inventor rather than to the librarian. In fact many of the things which we do daily and hourly our predecessors could not do for lack of the means — telephone, for instance.”

These improvements of the industrial age facilitated a wide range of initiatives under Bishop's leadership — the acquisition and painstaking preservation of specialized collections such as rare manuscripts, maps, and papyri; the conversion of the card catalog to the LC classification system (completed in 1926); the first photographic reproductions (starting with photostats of the eighteenth-century Kentucky Gazette, a key source for historians of the frontier); the purchase of private libraries such as that of the French writer-historian Henry Vignaud, an expert on the era of European discovery; a massive reference collection encircling students in the Reading Room; and a growing compendium of materials generated by political and social radicals and contrarians that began with a gift from the anarchist-unionist and collector Joseph Labadie.

(Sitting on the board of regents in the 1920s and '30s were three avid book collectors — William Clements, Lucius Hubbard and Junius Beal. That didn't hurt whenever Bishop needed support from on high. When the library director asked for a sabbatical leave in the mid-1920s, Clements wrote: "I know of no man who has been more devoted to the welfare of the university, and in particular the library, than Mr. Bishop.")

With the establishment of physically separate libraries for many of U-M's departments, colleges, and schools — medical, natural sciences, business, engineering, architecture, public health, music, education, dentistry, forestry, astronomy, physics, social work, economics — the library by the 1930s was no longer a building but a constellation. And in 1938, the collection hit the milestone envisioned when the new building opened — one million volumes.

A place for undergrads (and books)

By the time the U.S. entered World War II, more than 5,000 patrons, most of them students, were using the library every day — a far cry from the 1890s, when a bare handful of superstar pupils like William Bishop himself were granted special passes just to tiptoe into the stacks. During the war, patronage plummeted, but from 1945 on, returning servicemen funded by the G.I. Bill swelled student ranks beyond any number imagined in the days of Raymond Davis, who had left every summer to escape "the almost feverish rush of university life." Even as the library's leaders struggled to keep up with a postwar explosion of books and periodicals, they had little choice but to focus on a new priority — students, students, students.

So in 1956, Library Director Frederick Wagman unveiled spacious plans (by the Kahn firm again) for an Undergraduate Library to stand just to the east of what would now be called the Graduate Library, with a collection of 375,000 books. At 8 a.m. on January 16, 1958, the first patrons found amenities worthy of a student union — typing rooms, a coffee shop, an audio room, lounges, and — to the particular delight of summer-schoolers — air conditioning.

And of course it did not solve the old, familiar problem. The demand for new materials was a tide that only rose and never fell.

The best possible solution

Hardly had the Undergraduate Library (promptly dubbed the UGLI by the students who flooded it day and night) opened its doors before Wagman and his team had to begin thinking about another massive building project.

It was called "the best possible solution to an impossible problem."

As up-to-date as Albert Kahn's design may have been in 1920, by the 1960s the library was understood to be a stubbornly inflexible space — self-supporting stacks incapable of expansion plus public rooms where a lot of space was wasted. But the cost of tearing the old building down and building an entirely new one was judged to be intolerable.

Like a strapped family with more kids than bedrooms, planners concluded the only thing to do was add on out back.

This time the tab came to $5.5 million, paid for by a federal grant, a federal loan, and generous private donors. Again came the bulldozers and the cranes — taller cranes than the university had ever seen. The back of the library was torn off. Then its mammoth new appendage rose brick by brick and story by story until it was the biggest building on the Diag — another Kahn design, this one a strikingly modern contrast to the original. By the old standards, the statistics alone were staggering — seven floors of new stack space capable of housing nearly a million books; an eighth floor just for offices; 532 study carrels; 1,500 lockers; and a grand total of 132,866 square feet, with about 87,812 of those usable for actual library storage.

Naming it was a little tricky. Planners had referred to it simply as the "annex," but obviously that wouldn't suit such a massive addition. When it opened, it was baptized the Harlan Hatcher Graduate Library, honoring the Ohio State alumnus who was the university's eighth president (1951-1967). But the annex was seamlessly attached to the old "General Library," so what was its name now? Finally, with a shrug, the whole conglomerate was re-designated the Harlan Hatcher Graduate Library. Students just said "the Grad." Librarians used the shorthand "Hatcher North" and "Hatcher South."

It was dedicated in 1970.

In the new era to come, despite the digitization of much of the physical collection and the growing reliance on born-digital research materials that don’t require stacks and shelves, the library’s physical collection would continue to grow each year, and the struggle for books would endure.

Vintage postcard of the General Library building, ca. 1900