Ortelius atlas, part 1: The first modern atlas

November 5, 2025

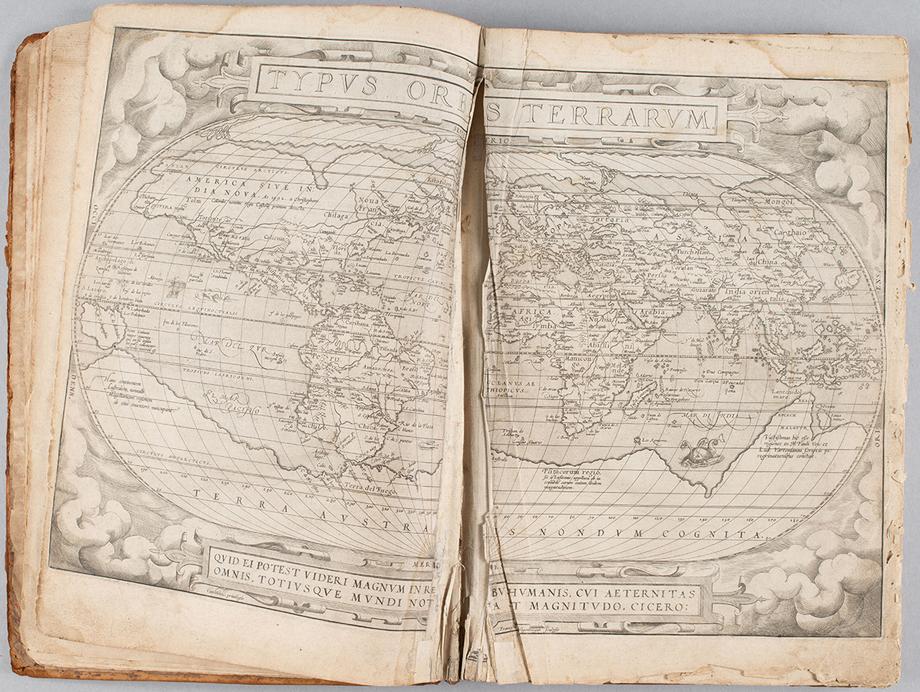

A few years ago, the U-M Library acquired Abraham Ortelius’s "Theatrum Orbis Terrarum" (Theater of the World), an atlas that revolutionized map making when it was first published in 1570 by presenting a global compendium of 16th-century cartographic expertise in one volume.

The library's copy is extraordinarily rare, being one of the first forty ever printed. It's also in need of extensive conservation and repair.

This is the first in a series of stories and videos about the atlas, its creator and many contributors, the provenance of the library's copy, and the work of the Conservation Lab to make it available to the research community. You'll find future segments on our website.

The first modern atlas

Maps are much more than mere navigational aids or guides to understanding the geography of a place. They are repositories of the worldviews, priorities, and geopolitics that influenced their makers. They influence how the people that use them perceive the world beyond what they can see. They offer snapshots in time, allowing us to track changes in landscapes, land use, human habitation, political and cultural identities, and more, making them relevant to many fields of study including the natural and social sciences, the arts, and urban planning, as well as geography and cartography.

Humankind has been making maps since ancient times, and the pioneers in cartography — whose methods were equal parts art and science — continue to influence the technology-driven navigational tools we use for wayfinding in the modern world.

Among the most notable mapmakers in history is Abraham Ortelius. Born in 1527 in Antwerp, a booming cosmopolitan center of trade, the arts, and printing, Ortelius would create what many experts consider the first modern atlas.

Describing the world

Atlases have existed since ancient times, but until the 1500s they looked very different from what we mean by the word today, said Anna Rohl, the library's map curator.

“The most famous classical atlas in the west is Ptolemy’s Geographia (circa 150 CE) but there is ongoing debate about whether the original even had maps in it,” she said. "Most of the book is text that lists around 8,000 place names and their locations, followed by a discussion of the mathematics of making accurate projections. Like many of the rediscovered classical texts that fueled the early Renaissance, Ptolemy’s work was kept alive by Muslim scholars in the Middle East during the Middle Ages. Starting in the 15th century, those map projections and locations were used by European mapmakers to create Ptolemaic atlases of the known world, but they usually included just 27 maps."

The Print Revolution that began with widespread use of the printing press in Europe in the 15th century spurred a new era in cartography. There was also a new hunger among an increasingly literate populace to see representations of the entire world, large parts of which were, from their perspective, newly discovered.

To meet this need, various kinds of books of maps began to appear, volumes that bound together various printed maps, charts, and (sometimes) texts. But these somewhat ad hoc productions didn't meet the need for a cohesive set of maps alongside text to help people make sense of them.

In the 1560s, Ortelius was inspired to begin work on a project that would remedy that gap.

“His was the first printed atlas containing maps designed to be seen together, and where the maps were the centerpiece, not just illustrations to accompany text,” Rohl said. It also brought together the best geographic knowledge then available in the western world, and included text describing the places depicted, Rohl explained. "It offered readers a lot of geographical and cultural knowledge, all in one volume."

From its first printing in 1570, the Theatrum was wildly successful — the best selling book of the second half of the 16th century, despite being one of the most expensive. Ortelius repeatedly reissued and expanded his atlas (there are 31 editions altogether, and it was translated from Latin into six languages), and it remained in print until 1612, more than a decade after his death in 1598.

Conservation of the U-M copy

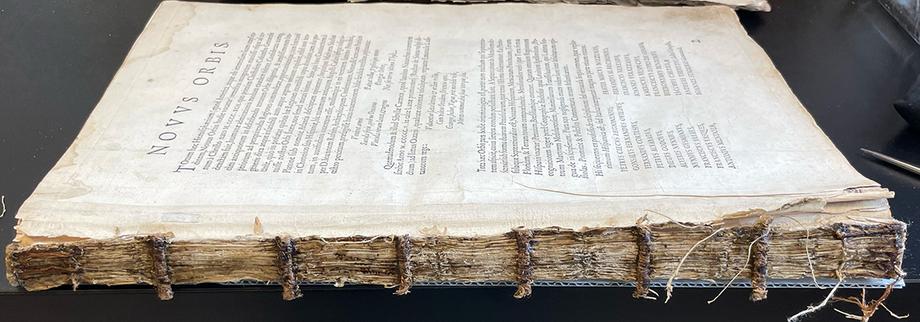

The library's copy is special, but it's also in poor condition — the leather cover, which is not original, has deteriorated, there are tears in the paper, and parts of the spine are missing.

Trina Parks-Matthews, assistant book and paper conservator, explained that previous repairs are actually now causing more damage.

“The atlas's paper has become brittle over time in part due to acid degradation. It's also thinner and weaker than the stiff repair paper, causing issues when the book opens," she said.

“The original paper and the mend move differently, causing tension and stress that can lead to further damage. This tension is further exacerbated by the already poor movement of the spine due to inflexible sewing,” she added.

After a thorough assessment, U-M library conservators and curators agreed that an interventive, or extensive treatment is merited in order to preserve the atlas.

The book will be completely disbound, the maps will be washed, old repairs removed, and tears mended with more appropriate materials. Then it will be rebound using new materials (the original materials will be retained for study).

“We will reduce brittleness and add flexibility to the paper by washing out the acid degradation byproducts and mending the tears with compatible materials that will flex and move together," Parks-Matthews said. "The new binding will be specially designed to allow the maps to safely open 180 degrees for reference and teaching.”

It's relatively rare to undertake such an extensive treatment on an item needing conservation, according to Parks-Matthews. But the atlas's high research and teaching value make it worthy of the investment in time and resources. Once the work is complete, she said, the community will be able to safely and responsibly use this very special book well into the future.

by Alan Piñon

Trina Parks-Matthews works on a page from the Ortelius atlas (Theatrum Orbis Terrarum).