Lessons from Galileo

October 20, 2022

Last June, curator Pablo Alvarez received a disconcerting email: a researcher who'd made a reputation identifying a famous forgery suspected that the library's treasured "Galileo manuscript" — with its notations on the earliest observation of the moons of Jupiter, a highlight of the history of astronomy collection that Alvarez curates — was a fake.

Thus began a journey of discovery, reconsideration, and revelation that would upend the item's place in the collection, and reinvigorate Alvarez's — and the library's — commitment to the pursuit of enduring truths.

It's an endeavor that Galileo himself would surely applaud, since he more or less invented it.

Galileo Galilei (1564-1642)

An Italian astronomer (among other things), Galileo was among the first to make a telescope powerful enough to point skyward to closely observe the night sky. Over the course of several nights in 1610, he observed several celestial objects near Jupiter, objects that seemed to move, even disappearing and then reappearing in such a way as could only be explicable if they were orbiting the nearby planet.

Galileo's discovery challenged scientific and religious beliefs that the earth was a fixed object around which all other heavenly bodies rotated. For decades, he defended his new heliocentric cosmology, writing to a friend, in a letter that circulated widely among interested parties, that the Bible was "an authority on faith and morals, not science."

His troubles with the Catholic Church's Inquisition, which in 1616 demanded that he cease to defend heliocentrism, came to a crisis in 1633, when he was compelled to publicly recant his discovery. As part of his sentence for having persisted in his views despite the Inquisition's condemnation, he spent the rest of his life under house arrest, and publication of any of his existing or future work was forbidden.

What we thought we had

Galileo's discoveries and ideas survived the church's attempt to suppress them at least in part because, a gifted writer and illustrator, he documented them so thoroughly. Many examples of his autograph writings — that is, handwritten by the author — survive, including books, letters, notes, and scientific observations.

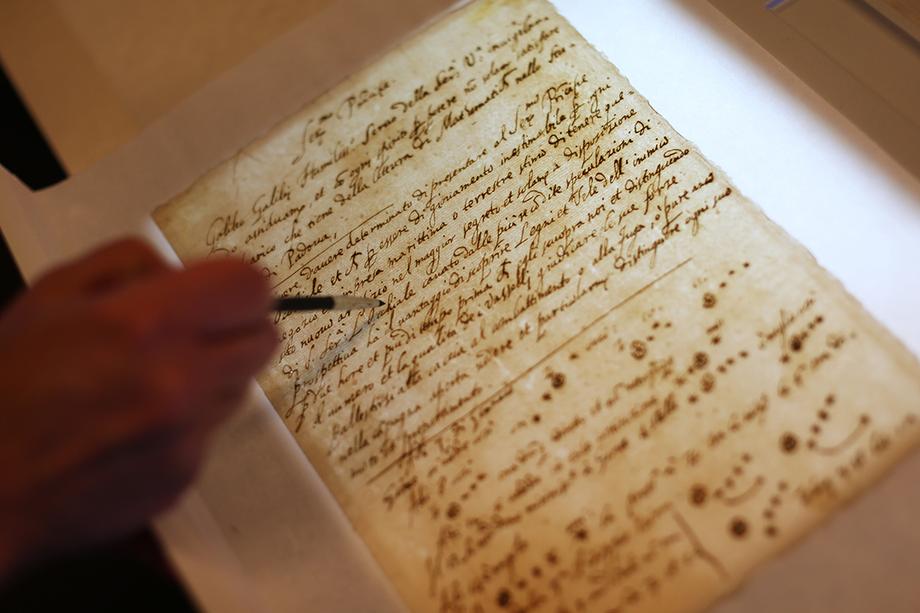

The library's Galileo manuscript was believed to be among them. It begins as a draft of a letter he sent to the Doge of Venice in 1609, touting his new and improved telescope and its potential benefits in warfare (the genuine, final letter is today held in the Archivio di Stato di Venezia). The bottom half contains draft notes recording those telescopic observations of the moons of Jupiter in January 1610 (the genuine notes and drawings are part of the Sidereus Nuncius Dossier at the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze.)

Based as it was on actual works that Galileo penned, the manuscript implied a story: that Galileo, in the midst of first observing the strangely-behaved stars that turned out to be Jupiter's four largest moons, reached for some scratch paper that contained a rejected draft of an important letter of business.

A fraud detected

The manuscript first came to public attention in May 1934, when the auction firm American Art Association, Anderson Galleries was selling the library of the late Roderick Terry, a wealthy collector of manuscripts and early printed books. According to the auction catalog, the manuscript was authenticated by Cardinal Pietro Maffi (1858-1931), Archbishop of Pisa, who compared it to two Galileo manuscripts in his own collection. It was acquired by Tracy McGregor, a Detroit businessman and avid collector of books and manuscripts. In 1938, two years after his death, the Trustees of the McGregor Fund bequeathed the manuscript to the University of Michigan, in recognition of Heber D. Curtis, professor of astronomy.

Since then, the Galileo manuscript at U-M has held a special place in the collection, and it was, along with the documents at the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, of great interest to researchers around the world. Locally, it was a highly-valued item, treated with extraordinary care by the library's conservators, and often shared by Alvarez during class visits to the Special Collections Research Center.

Then came that email, sent to Alvarez by Nick Wilding, a professor and historian at Georgia State University who had already identified one fake — a purported proof copy of Sidereus Nuncius (1610), Galileo's first publication of his celestial observations. Wilding, while researching his forthcoming biography of Galileo, could not square some notable contradictions between the U-M document and Galileo's other recorded observations and wanted a closer look.

“I knew the Ann Arbor document and had never been able to understand how it related to the logbook manuscript in Florence [the Sidereus Nuncius Dossier], so I decided to look closer, and came across this internal problem of two sets of observations, directly contradicting the logbook and historical reconstructions, requiring historians to claim that Galileo had, essentially, falsified them at a later date," Wilding explained. "That didn't make much sense to me.”

To get to the bottom of this mystery, Wilding asked for an image of the paper's watermark (watermarks served as trademarks for the paper mills of the era, or as identifiers for different batches or grades of paper). This watermark, barely visible even with special lighting, contained the initials "AS" and "BMO."

Wilding sent the image, without identifying its source, to two paper experts, both of whom dated the paper to the end of the eighteenth century, and thus impossible to have been in Galileo's supply. And when he searched for other documents with those watermarked initials, he re-encountered another purported Galileo document, dated 1607, which had appeared on the program Antiques Roadshow in 2015.

“This bothered me when it first surfaced because the text was copied from a facsimile of a known, lost letter, but subtly adapted," Wilding said. "When that document, now in the Morgan Museum in New York, revealed similar 'AS' and 'BMO' monograms, I realized that the Ann Arbor and the Morgan document were siblings, and both must be forgeries.”

Further research on the provenance of the U-M letter led Wilding to Cardinal Maffi's archive in Pisa, which led in turn to the finding that the two manuscripts were donated by one Tobia Nicotra, a name that Wilding had definitely heard before.

The forger

Nicotra was an Italian forger — infamous, prolific — whose life and exploits are, like his creations, rife with fabrication. What is certain is that he created and sold several forgeries as authentic Mozart and Giovanni Pergolesi autograph compositions, including some sold to the Library of Congress, the Metropolitan Opera Guild, and even to the library in Pergolesi's hometown of Pergola.

Some credit Nicotra with successfully forging more than 600 documents before he was caught and jailed for his efforts, but Wilding doubts that Nicotra was as prolific as that, just as he doubts a story that Nicotra had, at one time, seven apartments, each housing one of his mistresses.

But Nicotra was certainly a successful forger who went about his business in ways that made him hard to catch.

“He didn't suddenly flood the market with twenty dodgy Mozarts and nothing else, which would have required a really good backstory," Wilding said. "He also seemed to have sold directly to individual collectors rather than to dealers, and this cut down on the chance of being caught, as dealers talk to each other a lot.”

Nicotra was also smart in deciding what to forge, said Wilding. Nicotra's forgeries “don't make outlandish claims; they fill gaps, they anticipate desire. They are things that might have existed, and now do.”

This canny approach may have arisen from Nicotra's dual passions, interests beyond financial gain that may have directed at least the specialty areas for his forgeries.

The first of these was music. Wilding notes that Nicotra, who struggled to succeed as a musician, may have been seeking entry into that world. His first foray into fraud was an unauthorized and error-ridden biography of Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini, and he is believed to have traveled to the United States while impersonating the Italian composer Riccardo Drigo, several years after Drigo's death.

His second passion was Italy. Wilding thinks there's a political element in Nicotra choosing Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Galileo as his subjects. "He seems to have been an ardent Fascist, having been released from jail early to forge signatures for Mussolini's National Fascist Party. And after the war he published some peculiar pieces on Dante and ancient Rome that are full of nostalgia for a lost Italy. Forgery might have been his way of contributing to Italian nationhood."

How did we miss it?

The library had verified the manuscript’s provenance, and the document was examined by various experts in the years since it was acquired. The fact is, the forgery is a good one, according to Wilding.

“Hindsight makes most forgeries look shoddy, but there's nothing obviously wrong, materially or textually, with most of Nicotra's forgeries," he said. "The Michigan document is good because it's so presentable, so photographable — it's a made-for reproduction image, possibly because it was made from photographic facsimiles."

Add to this that most researchers looking at the manuscript were interested in what it said or how it said it. And what it said, aside from the discrepancies in the images Wilding saw, was consistent with what is known about Galileo and his findings.

None were trained to consider the paper to test the document's authenticity.

“Watermark study was not an important conceptual category for Nicotra or Terry or Maffi or MacGregor or, indeed, any of the historians who have written about the manuscript since its emergence,” said Wilding.

The only prior documented observation of the manuscript's watermark was by Paul Needham, author of a book about the making of Sidereus Nuncius. He notes that the watermark on the U-M document had not been found in other manuscripts by Galileo, but makes no inference about fraud because of it.

Wilding also posits that the U-M manuscript told a story too good and too powerful to be second guessed.

“The Ann Arbor document serves as an icon, even a thumbnail image, of the Scientific Revolution. It reveals our desire, and the desire of historians and collectors in the early twentieth century to possess and display genius at work. And it's done that job beautifully,” Wilding said.

Celebrating the truth

Galileo's most important legacy is the scientific method — roughly speaking, observe, hypothesize, test, repeat. Using this method, he made discoveries that were unwelcome to powerful people, and in consequence his life was threatened and constrained.

Fortunately, the library faced no dire consequences for revealing the outcome of a process — Wilding's observations and hypothesis, tested by various experts — that is by definition iterative, and always open to new information, methods, and perspectives.

“It was never about how to spin or minimize this discovery so as not to harm the reputation of the library or the university,” said Donna Hayward, interim dean of libraries. “In fact, after we got over the initial shock, we turned directly to making the new information widely available, in keeping with our mission to discover and share."

Because of all of this, because of what it represents, the document will continue to occupy a special place in the library's collection, beyond its usefulness to researchers.

Alvarez, who reports that faculty are now using the document to illuminate historical paper making, ink composition, paleography (the study of handwriting), and watermarks, has recovered from his initial reaction to the discovery.

“In Spanish, there is a saying: el tiempo lo cura todo, which means time cures everything,” Alveraz said. “When it was conclusive that the manuscript was a forgery, I felt extremely sad, disappointed, and frustrated. My thoughts were focused on my responsibility as a curator. How did something like this happen? Why didn't I ask all the right questions before?"

But as time passed, Alvarez came to appreciate the learning and teaching possibilities in Wilding's discovery.

“Nick's process in discovering this forgery is extremely interesting. If we are able to explain it to students, faculty, and the general public responsibly and accurately, I think we can make a very useful teaching tool, a sort of cautionary tale, a story to show that rigorous research in the humanities is the only tool to find the truth,” he said.

Wilding, for his part, appreciates the new, clearer view of Galileo's authentic works. “The story of his swift identification of a lunar system centered on Jupiter is no longer disrupted by the contradictions of the Ann Arbor manuscript,” he said.

“Now, we can get on with what we know to be true.”

by Alan Piñon and Lynne Raughley

Nick Wilding, Georgia State University.