Kasdan archive comes home

November 11, 2025

Screenwriter and director Lawrence Kasdan, who's been nominated for four Academy Awards (for The Big Chill, The Accidental Tourist, and Grand Canyon), and who also played a role in creating two of Hollywood's most successful franchises (Raiders of the Lost Ark and Star Wars), knew from an early age what he wanted to do with his life. That ambition brought him to the University of Michigan as an undergraduate.

Today, Kasdan is the most successful filmmaker ever to have graduated from the university.

And now his papers — which document the making of some of the most significant films of the last half century — have come home to the University of Michigan Library's Screen Arts Mavericks and Makers Collection. Kasdan is the first Michigan alum represented among a cohort that also features Orson Welles, Robert Altman, John Sayles, Jonathan Demme, Nancy Savoca, and Alan Rudolph (among others).

His Michigan connection isn't Kasdan's only point of departure from the rest, according to collection curator and Film Studies Librarian Philip Hallman. "His career is distinct in many ways. Unlike the others, he worked within the studio system, but unlike most within that system, he was able to direct his own screenplays, and so his films are very much infused with his unique viewpoint and vision."

See the report by the Associated Press, which includes video of an interview with Kasdan and an inside look at the archive.

Why Michigan?

When he was thinking about where to go to college, a friend (a Michigan alum) told him about the writing prizes given by the university's Hopwood Awards Program. And that playwright Arthur Miller had funded his undergraduate education with his winnings. Paying his way via his writing was an appealing prospect, and also a mark of early confidence in his abilities.

Kasdan (BA 1970, MA 1972) won four Hopwoods during his time at Michigan, which provided critical but insufficient funds; he still needed part-time jobs to get by. And yet, he still made time for the Cinema Guild — a student-run organization that screened a wide range of films at a time when it would have been otherwise almost impossible to see anything other than current Hollywood releases.

"It was a crazy, wonderful time,” he says, during which he was watching as many as ten movies a week. The guild was as crucial to his education as anything that happened in the classroom. Coming from a small town in West Virginia, for him, "it was like a starving man suddenly offered all this stuff to eat."

Foreign films, genre films, screwball comedies — he loved them all and would reprise and renew many of those genres in his future work.

In fact, Hallman credits Kasdan's wide-ranging appetite for shaping a career that refused to tie itself to one particular style or mode of storytelling. "Moviegoing for him was about all the different genres — Westerns, screwball comedies, film noir, old-school serial dramas — and he used aspects of all of them in the stories he wanted to tell," Hallman says.

At Michigan, Kasdan also found Kenneth Rowe, still teaching the playwriting seminar that Arthur Miller credited as having put him on the path to his own successful career. Rowe, he says, taught him about structure and eased his way by being a "benevolent professor, like something out of a 1940s movie."

"Very rarely a straight line"

Kasdan's home office features a collection of framed movie posters, including one for the acclaimed film Yojimbo by director Akira Kurosawa. That poster bears a fake director’s signature, a joke from one of his writer friends. "Actually, I did meet him once. But there was no poster exchange." As proof, he produces a photo of his younger self, shaking hands with the famous Japanese filmmaker. This kind of turn is familiar to Kasdan. Stories, he says, "are very rarely a straight line."

One might imagine his own career was pretty linear if you look at his string of films in the 1980s and 90s. After selling his first screenplay, The Bodyguard, in 1977, he wrote and directed Body Heat, released in 1981; then The Big Chill (1983); Silverado (1985); The Accidental Tourist (1988); I Love You to Death (1990); Grand Canyon (1991); and Wyatt Earp (1994).

It's a breathtaking run, launched in part by Steven Spielberg's enthusiasm for his script, Continental Divide. Spielberg wanted Kasdan to bring that story’s contentious romance to a project he and George Lucas were developing. Spielberg took him to meet Lucas and producer Frank Marshall at Lucas's temporary office on the Universal Studios lot, where they talked for the first time about Raiders of the Lost Ark, and when the conversation ended there were handshakes all around.

"It was insane," Kasdan says now. Just weeks before, he'd been working in advertising. He walked off the lot with Marshall, who wondered aloud whether they'd just been hired. "I don't know," Kasdan said. "I guess when we get home, we'll find out."

Kasdan credits his quick ascension to directing his own work to Raiders. Soon, he was writing and directing Body Heat.

"I was thinking I would have to convince people that a writer could direct, because there were only a few lucky ones who got to do that," he says. "Instead, I was directing very shortly after I'd made it into the business."

But that seemingly meteoric rise was no straight line; it conceals a decade of rejection of screenplay after screenplay — The Bodyguard alone was rejected 67 times, he reports — written in the evenings or whenever Kasdan had time away from his day job in advertising.

He was able to persist in part due to those Hopwood Awards he'd received as an undergraduate. "There was never a day after I received that letter that I doubted I would be able to make my way as a writer," he said in 1999, when he returned to campus to deliver the annual Hopwood Awards lecture.

What's in the archive?

Hallman has been overseeing the work to organize and describe the contents of the archive, so that researchers have a sense of what's there before requesting access via the Special Collections Research Center.

The work is about one-third done, Hallman says. That means the papers for films from the 1980s will be available to researchers first. The remaining work should be completed in the next eighteen months. Among the riches are scripts that were never sold or produced, which might hint at intriguing possibilities, though Kasdan doesn't think there are any hidden masterpieces.

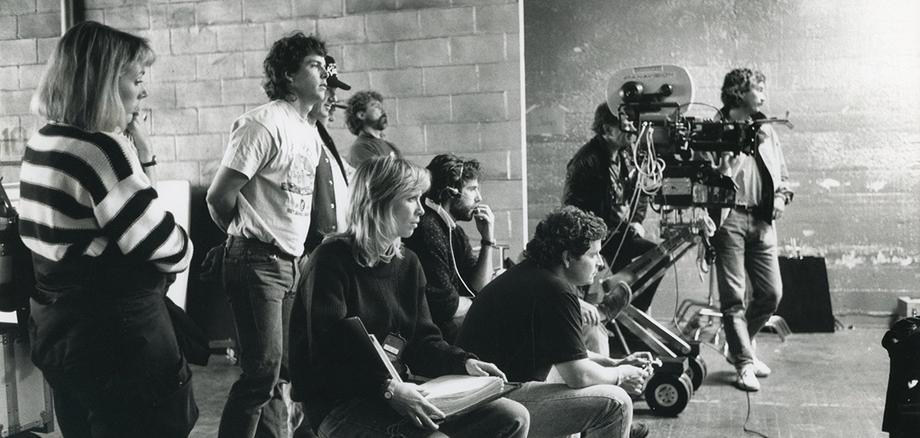

Amid the call sheets, scripts, and documentation of life on a film set, Hallman found photo albums depicting what Kasdan describes as "the families that were formed for each project," with many members — actors, crew, set designers, cinematographers, editors — staying on for the next one.

"I was never drawn to the popular Hollywood idea that conflict on a set makes great art," he says. He relies upon people he trusts to collaborate on solving the problems and issues that inevitably arise in a high-stress environment.

Hallman says the papers are extraordinarily well organized, which is pretty rare for an archive like this. Kasdan credits a cast of excellent assistants and also his own early interest in documenting his process.

"I valued the records, and I wanted them compiled into an archive in case someone wanted them. And I thought, if someone did want to explore it, it might as well be organized."

Music to a librarian's ears, and a gift to the researchers and future filmmakers who will most certainly want to explore it.

by Lynne Raughley

Screenwriter and director Lawrence Kasdan (1985).