History’s first drafts

December 14, 2022

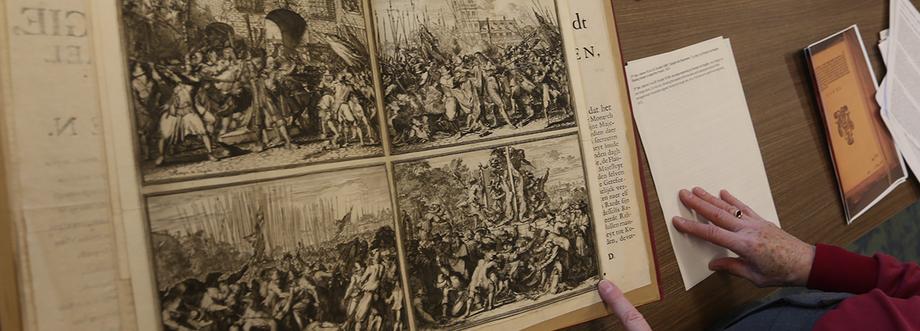

An intricate, four-panel print in a Dutch pamphlet published in 1672 portrays the gruesome deaths of Johan de Witt and his brother, Cornelis. Johan was the leader of the Dutch Republic during what is known today as the Dutch Golden Era. Blamed for a serious military defeat by their political opposition, the brothers were shot dead, then torn to pieces and cannibalized by an angry mob.

Another Dutch pamphlet, this one from 1599, features an intricate portrait of Queen Elizabeth I of England, dressed in an overflowing gown cinched tight at the waist, with ornate sleeves and a large neck ruff. The pamphlet details the treaty between England and the United Provinces of the Netherlands — the Treaty of Nonsuch — which pledged English aid to the breakaway provinces in their fight against Spain.

These Dutch historical pamphlets, often called tracts, were key transmitters of political and religious discourse among and across communities in the region from the 16th to 19th centuries. They were ephemera — produced in large numbers, meant to be read and passed along and eventually discarded. Their aim was to influence opinion or inform people about current events in a time long before social media.

The library is home to nearly 4,300 of these Dutch tracts, which range from a few to dozens of pages long, and often feature woodcut and copperplate prints engraved by important artists of the day: portraits, satirical vignettes, and maps, and even images of deaths by mob.

The value in such a collection is vastly expanded via a complete catalog. Karla Vandersypen spent 11 years as a volunteer, after retiring from the library, creating an online record describing each item in the collection. She finished the work in 2008, and probably knows the collection better than anyone.

The pamphlets capture key aspects of tumultuous times in the region, Vandersypen says. They also offer insights into how this early form of mass communication was used for propaganda purposes.

“Some historians of the Dutch pamphlets draw attention not only to their timeliness and propagandist approach, but also to the relative simplicity of their language, which made them accessible to a broad reading public," Vandersypen said. "The language of the vast majority of these pieces was Dutch, not Latin, which points to their intended audience.” Latin was the language of the educated elite, while Dutch was the language of ordinary people. The pamphlets were also priced so that craftsmen and merchants could afford to buy them.

Now, Ton Broos, professor emeritus of Dutch language and literature, is funding a project to digitize the pamphlets and make them searchable and readable online in the HathiTrust Digital Library. As part of the project, the pamphlets will be disbound (they're currently bound into volumes containing 25-30 pamphlets each) and re-housed as individual items.

Broos thinks the collection will be useful to historians, linguists, historical city planners, economists, doctors, literary historians, book historians, and others.

After all, the Low Countries (the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg) in the 17th century were known as "the bookshop of the world," Broos said. And these pamphlets — the products of a then-new technology, the printing press — were mass communication that chronicled and often drove the era's many disruptions to civic and religious life.

“It is not very difficult to find in these pamphlets and tracts points of contact with the world today and the many problems and questions that are of interest to researchers and students,” he said, mentioning, among other things, propaganda, ideology, censorship, and the separation of church and state. The pamphlets, like so much primary source material, demand, and will reward, painstaking and detailed study.

By helping to digitize the collection, Broos hopes to extend the opportunity for this kind of study to interested researchers everywhere.

by Alan Piñon & Lynne Raughley

Karla Vandersypen (left) and Ton Broos examine a Dutch pamphlet.