Conserving a medium that’s also a message

December 12, 2024

In behalf of my people, the American Indians, I hereby declare to you, the pale-faced race that has usurped our lands and homes, that we have no spirit to celebrate with you the great Columbian Fair now being held in this Chicago city, the wonder of the world.

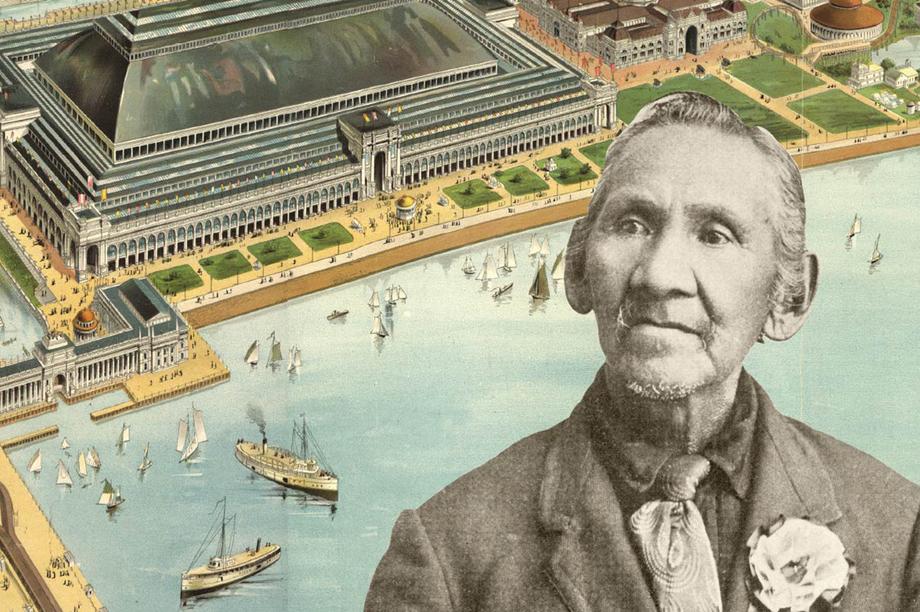

So begins "The Red Man’s Rebuke" by Simon Pokagon, a sixteen-page book that directly addresses the (mostly white) visitors to the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, also known as the World’s Columbian Exposition.

The fair marked the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the new world, and among the exhibits were replicas of Columbus’s ships, the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa María, which had triumphantly sailed across the Atlantic Ocean from Spain.

During this six-month long celebration in a city whose name derives from a Neshnabémwen word (zhegagosh, meaning place of wild onions), at least one event challenged the happy narrative of exploration, progress, and prosperity.

The author

On the busiest day of the fair, Simon Pokagon of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, spoke before the crowd, sharing his perspective of Indigenous peoples’ post-Columbian experience. In "The Red Man’s Rebuke," which was offered for sale, Pokagon vividly recounts how their lands, families, and ways of life had been destroyed:

But alas! the pale-faces came by chance to our shores, many times very needy and hungry. We nursed and fed them,—fed the ravens that were soon to pluck out our eyes, and the eyes of our children; for no sooner had the news reached the Old World that a new continent had been found, peopled with another race of men, than, locust-like, they swarmed on our coasts; and, like the carrion crows in spring, that in circles wheel and clamor long and loud, and will not cease until they find and feast upon the dead, so these strangers from the East long circuits made, and turkey-like they gobbled in our ears, “Give us gold, give us gold”; “Where find you gold? Where find you gold?”

Recognized in his time as an influential Indigenous advocate, he pressed the U.S. government to fulfill its treaty obligations, met with two U.S. Presidents (Lincoln and Grant), and achieved status and praise in elite literary circles. He also possibly exaggerated his educational achievements, was susceptible to some dubious notions redolent of eugenics, and may have crossed some ethical lines when managing tribal property on the Chicago lakefront.

His Wikipedia page calls him an “ambiguous icon… who obtained ‘celebrity’ status.”

Today, readers, scholars, and researchers do the important work of finding out all they can about Pokagon’s life and his work, both because of what they meant in his time, and because of what they mean in ours.

The birch bark books

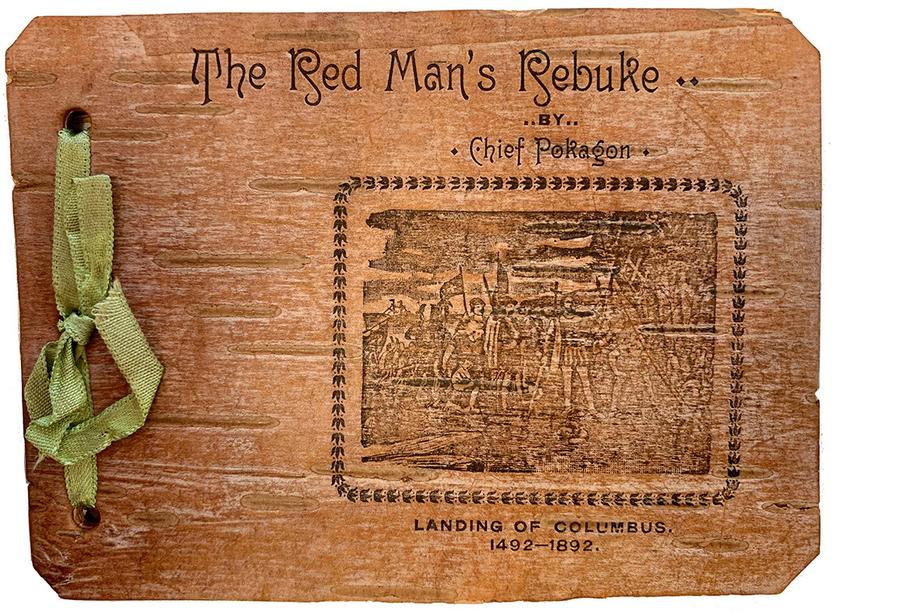

Among Pokagon’s legacy is a collection of four birch bark books: "The Pottawatamie Book of Genesis: Legend of the Creation of Man," a Potawatomi creation myth; "Algonquin Legends of Paw Paw Lake," an account of a long-ago breach in a waterway for which there is some evidence in the geological record; "Algonquin Legends of South Haven," the story of an ancient Potawatomi kingdom; and "The Red Man’s Rebuke," some versions of which are titled "The Red Man’s Greeting."

These palm-sized illustrated books, made from thin layers of hand-harvested birch bark (which, done correctly, does not harm the tree), were published by C. H. Engle in Hartford, Michigan between 1893 and 1901.

Pokagon explained his choice of medium at the start of The Red Man’s Rebuke:

My object in publishing the “Red Men’s [sic] Rebuke” on the bark of the white birch tree, is out of loyalty to my own people, and gratitude to the Great Spirit, who in his wisdom provided for our use for untold generations, this most remarkable tree with manifold bark used by us instead of paper, being of greater value to us as it could not be injured by sun or water.

Out of the bark of this wonderful tree were made hats, caps and dishes for domestic use, while our maidens tied with it the knot that sealed their marriage vow; wigwams were made of it, as well as

large canoes that outrode the violent storms on lake and sea; it was also used for light and fuel at our war councils and spirit dances.

And though he doesn’t mention it, birch bark was also used to make the historic scrolls of his people, the Anishinaabe (a group of Great Lakes Indigenous people, also known as the People of the Three Fires). These texts, which document the Anishinaabe migration story via pictographs, and which also record their spiritual ceremonies, are held sacred by the descendants of the people who made them. Many of them fell into the hands of others — mostly white settlers — as a result of upheaval and genocide in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Today, there is an urgent and sometimes contentious movement among Indigenous people to recover cultural and spiritual artifacts from private collections, museums, and libraries. These repatriation efforts are part of a broader endeavor to reclaim their places in the past, present, and future of their various nations.

To a large extent, Pokagon’s birch bark books stand apart from this. Though the stories they tell, as Pokagon writes, are “as sacred to us as Holy Writ to the White man,” they were squarely aimed, both in their storytelling and their form, at white people, who probably bought them as curiosities and souvenirs at least as often as for reading material.

It’s impossible to know how many of these books remain. According to WorldCat, the number of libraries that hold one or more copies is in the tens. The U-M Library holds one copy each of "The Red Man’s Rebuke," "Pottawattamie Book of Genesis," and "Algonquin Legends of Paw Paw Lake" (the Bentley Historical Library also has a copy of "Rebuke").

How they arrived is unknown, but after more than 50 years of service in the university’s learning, teaching, and research, these still-sturdy books were in need of expert treatment.

The conservator

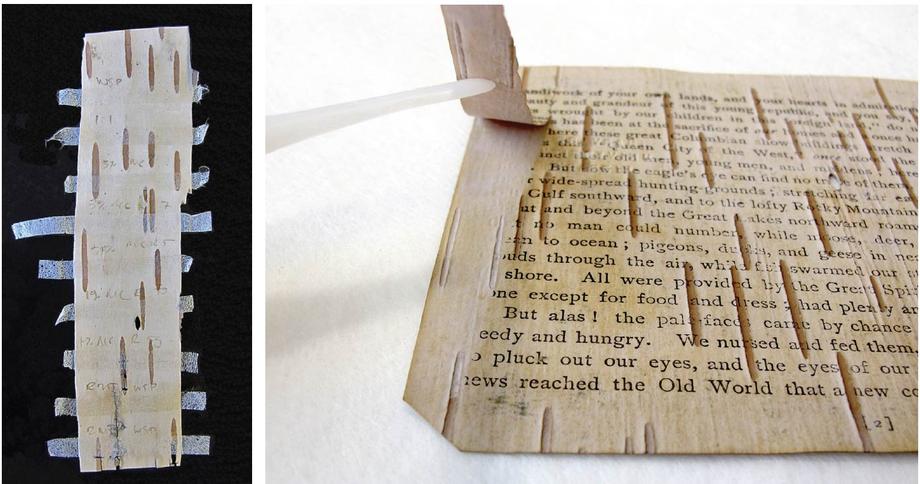

The books range from ten to sixteen pages, and were originally bound by green silk ribbon running through three punched holes on the left edge (these bindings have since failed). The pages themselves, still quite sturdy, vary in thickness, color, and wood grain, and their text and illustrations were printed in black ink by a letterpress machine.

Although they’re not considered sacred, conservator Marieka Kaye, the library’s director of preservation services for physical collections, approached the project with what can only be called reverence.

“I’m honored,” she said, “to be able to repair Simon Pokagon’s books so that students, faculty, and researchers can learn from them for many more years to come.”

She has an upper midwesterner’s feelings about birch bark. “It’s something that many of us grew up surrounded by — as kids we peeled the bark ourselves, as it looks so inviting on the tree — and some of us may have even tried to write or draw on it. It makes people want to touch and hold it, and it has a lot of power that way.”

She also knows it has ongoing importance to the Indigenous communities that relied on it for generations. “It remains integral to their culture to this day, although the trees, like so much of our natural world, are constantly under threat.”

Tempting though it may be, unless you’re an expert you shouldn’t attempt to remove birch bark directly from the tree; unless you do it correctly, you can harm or even kill it. The relevant expertise is a collection of knowledge, practices, and beliefs known as Traditional Technical Knowledge, which Indigenous people have developed over time through direct interaction with their environment.

The good news is that birch trees naturally shed bark as they grow, and it’s fine to harvest what you find on the ground.

In planning for the treatment of the books, Kaye engaged in a multifaceted interdisciplinary research project that involved a deep dive into the chemistry of birch bark, consultations and symposia with other expert conservators, conversations with contemporary Indigenous artists and tribal representatives, and even treks through birch forests in Northern Michigan.

Kaye said, “Conservators of library and archival collections must understand the chemistry and working properties of the materials people use to create books, as well as why they were made and who used them. We seek to learn about the items we treat in the deepest way possible.”

In that light, Kaye consulted Ben Secunda, managing director of the U-M Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act Office, to ensure the conservation work respected cultural guidelines.

She also examined other birch bark books and ephemera, including some belonging to the Bentley and Clements Libraries, that were not created by Indigenous people. These items, Kaye said, “informed my understanding of the materiality and preservation of birch bark as a writing or printing substrate.” They also helped her see how birch bark materials aged, placed Pokagon’s works in the context of the Victorian tourist trade, and advanced her understanding of how white settler communities appropriated the Indigenous use of materials for their own gain.

Kaye’s expansive approach — this inclusion of informants and collaborators from a wide range of institutions, locales, and cultures — is largely representative of how librarians, curators, and conservators go about their work. Though they’re often fiercely protective of the materials for which they are directly responsible, they also recognize that these holdings are humanity’s collective heritage.

Kaye repaired tears in the pages of "The Red Man’s Rebuke" by applying a thin, transparent, lightweight Japanese paper with a water-based adhesive that dries without distorting the text or texture of the pages. For now, the book remains unbound, making it easier to exhibit (several pages were displayed in a fall 2024 exhibit in the Stamps Gallery).

The last word

Pokagon had much to say on the subject of threats to the natural world, which was one among many injuries done to his people by white settlers. His lamentations in these books are shot through with disappointment that the people proselytizing Christianity to tribal peoples so often failed to live by its tenets.

Many among his band were Catholic, including Pokagon himself, and it’s not always possible to draw a sharp line in his writing between Indigenous spiritualism and a Christian God. For example, he ends "The Red Man’s Rebuke" with a promise of retribution and justice, delivered by the Great Spirit to the faithless “sons and daughters of the east” who seem to reside in a post-apocalyptic Christian kingdom.

“Therefore know ye, this much abused race shall enjoy the liberties of these happy hunting-grounds, while I teach them my will, which you were in duty bound to do while on earth. But instead, you blocked up the highway that led to heaven, that the car of salvation might not pass over. Had you done your duty, they as well as you would now be rejoicing in glory with my saints with whom you, fluttering, tried this day in vain to rise. But now I say unto you, Stand back! you shall not tread upon the heels of my people, nor tyrannize over them anymore. Neither shall you with gatling-gun or otherwise disturb or break up their prayer-meetings in camp any more.

Neither shall you practice with weapons of lightning and thunder any more. Neither shall you use tobacco in any shape, way, or manner. Neither shall you touch, taste, handle, make, buy, or sell anything that can intoxicate any more. And know ye, ye cannot buy out the law or skulk by justice here; and if any attempt is made on your part to break these commandments, I shall forthwith grant these red men of America great power, and delegate them to cast you out of Paradise, and hurl you headlong through its outer gates into the endless abyss beneath — far beyond, where darkness meets with light, there to dwell, and thus shut you out from my presence and the presence of angels and the light of heaven forever and ever.”

Powerful words in any medium. Ensuring that we can continue to read them as originally published, on pages made from the bark of a tree that has sustained the writer’s people for centuries, is the library’s responsibility and its privilege.

Find out more

- See the Smithsonian’s digital copy of The Red Man’s Rebuke.

- Read Conservation and Study of Simon Pokagon’s Birch Bark Books, an open access paper by Oa Sjoblom and Marieka Kaye that digs into the books’ history and construction.

- Read As Sacred to Us: Simon Pokagon’s Birch Bark Stories in Their Contexts, edited by Blaire Morseau, which includes summaries of the full text of all four birch bark books (Sjoblom and Kaye are among the contributors). Morseau, a citizen of the Pokagon Band and a professor at Michigan State University, positions the books as having “material effects on the possibilities Indigenous people envision for themselves while making space for Indigenous agency in the future.”

- Watch Bookworm 61, a conversation hosted by the William L. Clements Library featuring Blaire Morseau and Fritz Swanson. Swanson, director of the Wolverine Press, the publishing exploratory for the Helen Zell Writers’ Program, used the press’s equipment to study unanswered questions about the process of printing on birch bark.

by Mary Morris and Lynne Raughley

The Red Man's Rebuke, a birch bark book by Chief Pokagon, 1893 (image courtesy the Bentley Historical Library).