The art of the book

March 3, 2025

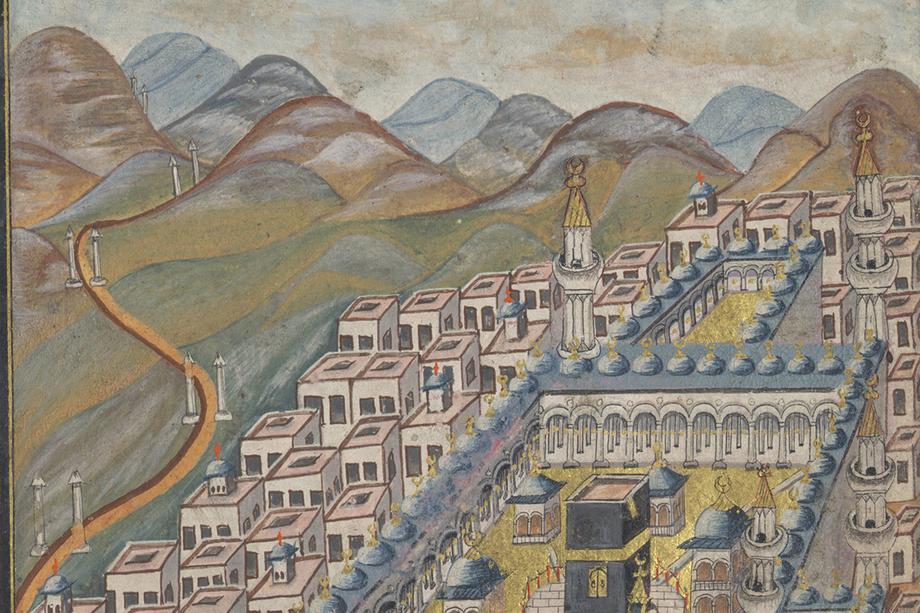

A small group of students in the Special Collections Research Center hover over ornate Islamic manuscripts from the 14th to the 18th centuries, often peering closely from just inches away, and gently turning pages that have survived for hundreds of years. They are looking for clues of sorts — and not just in the written text, but in the paper itself, or in the ink used, or in the way the script and images are arranged and presented on the pages. Under this close scrutiny, Remy Djavaherian, a fourth-year undergraduate at U-M, finds that these historic texts, even after all this time, hold much left to be discovered.

“Islamic manuscripts in a physical and cultural sense are alive. By that I mean that they are constantly changing, being physically modified as well as entering new cultural spheres and taking on different meanings and different levels of importance, giving them a life and a story to be discovered,” Djavaherian said.

The collection

The students are examining items from the library’s Islamic Manuscripts Collection, which consists of 1100 volumes dating from the 8th to early 20th century, and is among the most significant of such collections in North America.

The collection includes religious texts, including manuscripts of the Qur’an and its sciences, hadith, jurisprudence (fiqh), theology (kalam), and Sufism, but also works of mathematics, astronomy, philosophy, rhetoric, grammar, poetry, history, geography, and medicine — all in Arabic, Persian, or Ottoman Turkish.

The collection, which encompasses a wide range of script styles and binding techniques, is available to everyone via the HathiTrust Digital Library.

But while digital analogs serve an important purpose, nothing can replace seeing these works up close, turning their pages, and comparing and contrasting among them.

In this session, the students are exploring a selection of devotional manuscripts, primarily from Mamluk and Ottoman-era North Africa and Anatolia.

Islamic Manuscripts Collection Curator Evyn Kropf (also librarian for Middle Eastern & North African Studies and Religious Studies) is inviting them to consider how the distinctive layouts, functional ornaments, sizes, and scripts of these manuscripts are significant for the devotional practices they support, as well as how a devotee would interact with their texts, visual content, and physicality.

The seminar

Djavaherian and his classmates are studying these manuscripts for their Islamic Book Arts seminar, an upper-level History of Art seminar that teaches students about the history of knowledge and book production, especially in the Islamic world from the 7th century until today.

“In this class, students learn how to handle manuscripts and how manuscripts are made, including the production of paper, ink, pigments, and bindings,” said Christiane Gruber, professor of Islamic Art in the History of Art Department, who co-teaches the class with Kropf.

The students also learn how to recognize and decipher various Arabic scripts and better understand calligraphy, or the art of beautiful writing. They become familiar with illustration and illumination practices, as well as the production of texts that are religious (like the Qur’an), historical, diplomatic, devotional, and scientific.

The seminar draws a mix of students from across disciplines. Some are PhD students in History, Art History, and Middle East Studies. Others are master’s students in Global Islamic Studies or Information Science.

Djavaherian is a pre-med student majoring in Persian visual culture with a minor in Art History.

For Kyle Capps, a first-year doctoral student in the Middle East Studies department, the opportunity to have first-hand interactions with primary sources has been illuminating, especially for someone immersed in the study of the region and its cultures.

“I have been surprised by the wide range of cultural and artistic influences apparent within our sources. We looked at Timurid-era (1370–1507 C.E.) illuminated manuscripts from Iran. The use of color and gilding was beautiful in its own right, but the figures depicted within these illustrations highlighted an artistic influence emanating from Central Asia and China,” Capps said.

Capps explained that Timur and his successors, as Central Asian rulers of Iran, served as patrons for artistic works that featured imagery reminiscent of their homeland. From Tabriz, Iran, this art style spread across the Middle East, India, and North Africa.

“That kind of artistic influence may initially seem inconsequential, but when you see its impact within a wide range of other documents spanning centuries, you recognize a significant artistic impact of the Mongol conquests on the region,” Capps said.

Realizations like this — discerning the considerable ripple effects of artistic and cultural influences among documents that span a thousand years of history — are a key learning goal of the seminar.

“Students discover that one book represents an entire cosmos: it can tell a centuries-long story about how sacrality is materialized; how resources (like animals) are mobilized to make parchment and leather bindings; how pigments reveal long-distance trade in goods and materials; how marginal comments record the life of the mind; and how paintings reveal traces of their viewers’ devotional engagements,” Gruber said.

The session’s manuscripts

Many of the manuscripts of Qaṣīdat al-Burdah (Ode of the Mantle) — a well-known poem in praise of the Prophet Muhammad attributed to the poet and mystic, Sharaf al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn Saʻīd al-Būṣīrī (d. between 1294-7) — are notably large, produced to impress on occasions commemorating the Prophet’s birth or other rituals, for the Mamluk rulers of Egypt. Their distinctive layouts — shifting between large and small lines of stately script — make the Arabic text of the poem and its amplification immediately recognizable.

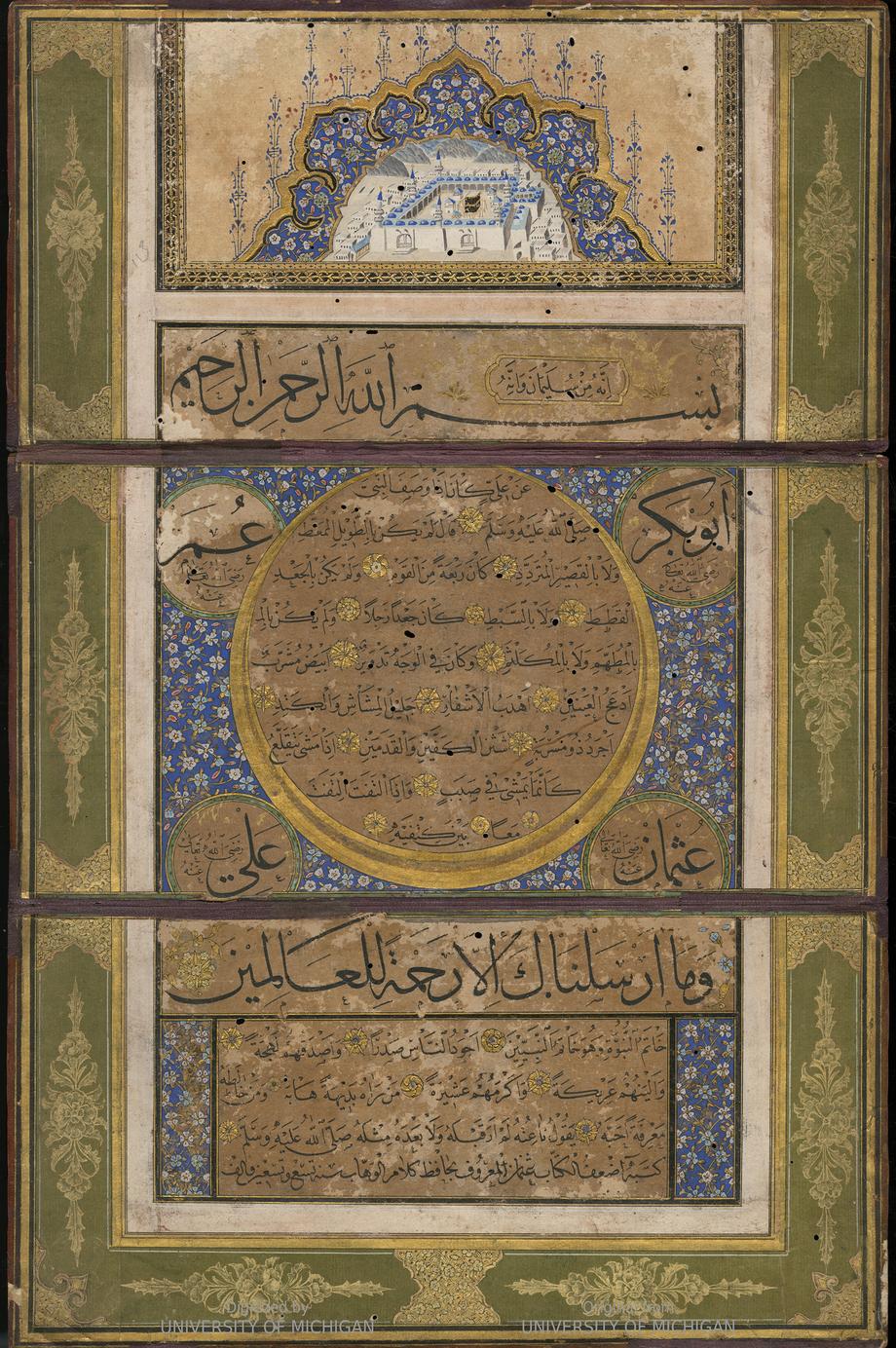

The manuscripts of Dalāʼil al-khayrāt (Guideposts to Goodness) — an enormously popular Arabic devotional compendium of blessings over the Prophet Muḥammad authored by the Moroccan mystic Abū ʻAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Sulaymān al-Jazūlī (d. 1465) — include functional ornaments to guide readers through the ritual portions of recitation. Complex layouts and contrasting inks invite concentration and focused contemplation, as with the presentation of the Prophet’s many names in one of the manuscripts. A note in the margin at the opening of the section discusses instructions for invoking these prophetic names.

The prayer compendia include a multitude of devotional texts — select chapters from the Qur’an, potent prayers, and significant images, among them the hilye-yi şerif, a kind of verbal portrait describing the Prophet Muhammad’s physical characteristics and moral attributes presented in a diagrammatic form invented by the Ottoman calligrapher Hafız Osman Efendi (d. 1698). A hilye panel by this master calligrapher is one of the most significant manuscripts in the entire collection.

Another slender volume with decorative elements characteristic of Timurid-era production includes only particular sūrahs (chapters) from the Qur’an, recited together on particular occasions. Such manuscripts were very popular in Turkish-speaking areas, and this manuscript contains inscriptions in Ottoman Turkish added by a later owner at the opening and close of the volume.

You can view and download most of the manuscripts at the HathiTrust Digital Library.

Our online guide to Islamic Manuscripts offers more information about the collection’s history, provenance, and contents, as well as the curator’s contact info.

by Alan Piñon

Students examine Islamic manuscripts.